| Welcome, Guest |

You have to register before you can post on our site.

|

| Online Users |

There are currently 679 online users.

» 11 Member(s) | 663 Guest(s)

Applebot, Bing, Facebook, Google, Twitter, Dana Scott, Daniele, E Lillie, eggyk, Kvncmd, NosDa

|

| Latest Threads |

“The Library of Babel” by...

Forum: Fiction, Comics, Films & Videos, Games & other Media

Last Post: ReneZ

5 minutes ago

» Replies: 8

» Views: 285

|

Elephant in the Room Solu...

Forum: Theories & Solutions

Last Post: Jorge_Stolfi

33 minutes ago

» Replies: 88

» Views: 5,004

|

Would a NEW Voynich Manus...

Forum: Provenance & history

Last Post: Bluetoes101

48 minutes ago

» Replies: 30

» Views: 793

|

On the word "luez" in the...

Forum: Marginalia

Last Post: JoJo_Jost

3 hours ago

» Replies: 7

» Views: 170

|

The Modern Forgery Hypoth...

Forum: Theories & Solutions

Last Post: R. Sale

4 hours ago

» Replies: 381

» Views: 35,361

|

A random rant about the V...

Forum: Voynich Talk

Last Post: JustAnotherTheory

5 hours ago

» Replies: 0

» Views: 62

|

Three arguments in favor ...

Forum: Theories & Solutions

Last Post: JustAnotherTheory

6 hours ago

» Replies: 13

» Views: 825

|

AI-generated "Voynich man...

Forum: Fiction, Comics, Films & Videos, Games & other Media

Last Post: Koen G

9 hours ago

» Replies: 109

» Views: 49,827

|

I found "michiton" in a 1...

Forum: Marginalia

Last Post: JustAnotherTheory

Yesterday, 11:58 AM

» Replies: 4

» Views: 209

|

I've never seen anyone ta...

Forum: Marginalia

Last Post: LisaFaginDavis

15-01-2026, 10:15 PM

» Replies: 3

» Views: 189

|

|

|

| [split] Torsten's criticism of Bowern & Lindemann |

|

Posted by: Torsten - 14-08-2024, 01:53 AM - Forum: Analysis of the text

- Replies (20)

|

|

[Edit KG: this thread split off from here: You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. ]

(14-08-2024, 12:50 AM)ReneZ Wrote: You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. (13-08-2024, 11:46 AM)Torsten Wrote: You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.The primary sources for the article appear to be interviews with Lisa Davis and Claire Bowern

You are guessing, and you are guessing wrong. I know of at least five people who have been involved, and there were probably more.

No guessing is required since the article is actually about Lisa Fagin Davis and her views about the Voynich manuscript. Yes, the article does mention other perspectives, including two sentences about Andreas Schinner and my research. But, the sole purpose of these two sentences is to serve as an introduction to Lisa Fagin Davis's perspective on our research. And I know for sure that Ariel Sabar never asked us about our research.

(14-08-2024, 12:50 AM)ReneZ Wrote: You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. (13-08-2024, 11:46 AM)Torsten Wrote: You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.For instance the article states "The mix of word lengths and the ratio of unique words to total words were similarly language-like." The contrary is true. The word length distribution matches almost perfectly a binomial distribution and is therefore not language like.

This suggests that there should exist a good test for what is language-lilke and what is not. Well I don't think so.

Stolfi did not write that the word length distribution is not language like, and anyway, Stolfi is not a linguist. Neither am I for that matter.

I can't decide for myself to what extent the text is language-like, but at first sight it is very language like, while in important details it is less so. Saying that it is not language-like would be more incorrect in my opinion.

Claire Bowern, a linguist, states: "Short words tend to be the most common words in natural language texts, but the most common Voynich words have four or five letters." [Bowern and Lindemann 2020].

In linguistics, the brevity law (also called Zipf's law of abbreviation) is a linguistic law that qualitatively states that the more frequently a word is used, the shorter that word tends to be. Zipf (1935) posited that wordforms are optimized to minimize utterances communicative costs (see You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.). For example, consider the length of frequently used words in English, such as "a", "is," or "I".

|

|

|

| descent with modification |

|

Posted by: obelus - 12-08-2024, 08:03 AM - Forum: Analysis of the text

- Replies (15)

|

|

Many thanks to the presenters last Sunday. Not only did they deliver new results, but subsequent discussion on the forum has been stimulating. For example, Torsten crisply summarized a prediction that follows from the self-citation hypothesis:

(09-08-2024, 03:36 PM)Torsten Wrote: You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view....the scribe might introduce new spelling variants. For example, he could decide to add [aiin] alongside [daiin]. This change would affect only the text generated after [aiin] was introduced, leading to observable developments in the manuscript. Decide for yourself whether the patterns observed in the Voynich text align with this description.

OK, let us attempt to decide on quantitative grounds.

The minimal model is a scribe working page by page from top down. Self-citation would begin with the top line of text, and introduce variants as new lines are generated out of words visible above. Therefore the text is predicted to deviate further and further from the first line as we advance down the page. Space-delimited "words" are the units of composition in this picture. So here is a first-pancake metric of wordwise similarity between lines:

Take each word of a non-page-initial line, and compute its minimum possible edit distance to a word in the initial line. (It is to be hoped that this minimal-edit selection correlates somehow, retrospectively, with the scribal method.) Calculate the Mean Minimum Edit Distance for the words in that line. In some rough sense the MMED score captures how directly the collective of words can be derived from the initial line. As we proceed down the page, more and more mutated versions of the first-line words are visible to the scribe, so the compounded mutations are expected to increase the MMED score as a function of line rank.

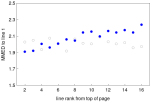

Happily Torsten has posted a a You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. that implements self citation. By chopping the generated text into 75 pseudo-pages of 16 lines each, we can approximate the bulk layout of a vms sample (below). The statistical traces of pagewise self-citation, if present, should manifest on each page independently. Therefore we stack all of the individual-page results together with a co-average representing each line. In the plot below, for example, the point at rank 2 represents an average of all 75 second lines' MMED scores relative to their own first lines, etc etc:

generated_text.txt

This plot is not saying anything new or interesting about the text generator; it serves merely as validation of the MMED measure, showing that it can pick up a macro property that emerges from the word-by-word generation algorithm. The farther we progress down each page, the more the words deviate from their first-line exemplars. Open markers show the same calculation performed with words randomly shuffled among the available positions, in which case no trend is expected or observed. MMED values appear to saturate as more than 15 lines are included.

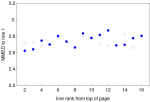

Finally, what the crowd paid to see: We repeat the analysis with paragraph text from Takahashi IT2a-n.txt, using 84 pages that contain at least 16 lines.

IT2a-n.txt

Oh well... I have not yet decided for myself whether the patterns align. The greater noise present in the real text might just obscure a trend of the magnitude seen in the synthetic text.

One way forward would be to refine the line-comparison function, in hopes of increasing its sensitivity, decreasing the noise, or accounting for reference lines other than the page-initial one.

Another is to observe the Perseids from a dark location; at mine the radiant is just now rising.

The initial line of You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. is

<f1r.1> fachys ykal ar ataiin shol shory cthres y kor sholdy

The first word of the next line <f1r.2> is sory, at Levenshtein distance 1 from shory in the line above. Averaging the minimum edit distances for all 11 words in <f1r.2> yields a MMED of 1.81. Collecting all 84 MMED values for the pages considered, the value plotted at line rank 2 is 2.63. |

|

|

| Voynich Manuscript Day 2024: videos |

|

Posted by: Koen G - 11-08-2024, 06:09 PM - Forum: News

- Replies (4)

|

|

Hi all,

I finished editing the videos for Voynich Day 2024. Here they are, in the same order they were presented during the event:

- tavie - You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

- Koen Gheuens - You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

- Rene Zandbergen - You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

- Patrick Feaster - You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

- Koen Gheuens - You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

- Cary Rapaport - You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

- Lissu Hänninen - You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

- Michelle Lewis - You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

- Emma May Smith - You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

Thanks to all participants for an excellent first edition. See you all next year for Voynich Day 2025!

|

|

|

| End--End Transition Probability |

|

Posted by: Emma May Smith - 09-08-2024, 11:24 AM - Forum: Analysis of the text

- Replies (4)

|

|

Inspire by Patrick's recent presentation I thought I would look at the transition probabilities of End--End pairs. These are the likelihoods (as a fraction of 1) that a word with a given ending will be followed by a word with another given ending. (I'm surprised nobody has done this before, so if they have, please do say.)

All numbers are from a selection of running text in Currier B. Only those word endings which occur at least 250 times have been counted, and results only show relationships at 0.05 or higher. Also, [in] was processed as a single glyph. The total likelihood for all the results given is in parentheses at the end.

[d]: [y] .46, [in] .17, [l] .14, [r] .12 (.89)

[l]: [y] .47, [in] .15, [l] .15, [r] .13 (.90)

[m]: [y] .31, [in] .25, [r] .14, [l] .13, [o] .05 (.88)

[in]: [y] .46, [l] .16, [in] .15, [r] .12 (.89)

[o]: [y] .32, [in] .19, [l] .18, [r] .17, [o] .05 (.91)

[r]: [y] .39, [in] .18, [r] .17, [l] .14 (.88)

[s]: [in] .33, [y] .27, [r] .16, [l] .13, [s] .06 (.95)

[y]: [y] .49, [in] .17, [l] .14, [r] .12 (.92)

My initial thoughts are that [d, l, in, y] are all very similar. [r] is a bit lower on [y] but not hugely different. But [m, o, s] are all quite variant. These are quite low counts (along with [d]), so it could be that there's simply a lot of spikiness in the data. Hard to tell  . .

Breaking the data down by bigrams for the first feature shows no big difference: [ol] and [al] are similar to [l], [or] and [ar] are similar to [r], [ain] and [iin] are similar to [in]

But the differences between [ey] and [edy] are worth breaking down, both as the first and second feature. Each occurs thousands of times: about 2,300 and 3,500, respectively. [$y] stands for some other word ending in [y], including [dy] not preceded by [e].

[edy]: [edy] .29, [in] .14, [$y] .14, [l] .13, [ey] .11, [r] .10

[ey]: [in] .20, [ey] .19, [edy] .15, [l] .14, [r] .12, [$y] .12

[d]: [edy] .21, [in] .17, [$y] .15, [l] .14, [r] .12, [ey] .10

[l]: [edy] .23, [in] .15, [l] .15, [$y] .14, [r] .13, [ey] .10

[m]: [in] .25, [r] .14, [l] .13, [edy] .11, [ey] .10, [$y] .10, [o] .05

[in]: [$y] .19, [l] .16, [in] .15, [edy] .14, [ey] .13, [r] .12

[o]: [in] .19, [l] .18, [r] .17, [edy] .12, [$y] .11, [ey] .09, [o] .05

[r]: [in] .18, [r] .17, [$y] .16, [l] .14, [edy] .13, [ey] .10

[s]: [in] .33, [r] .16, [l] .13, [$y] .11, [edy] .09, [ey] .07, [s] .06

This data looks a bit messy, but a few things can be seen: - [edy] clearly likes to cluster --- I think we already knew this.

- [l] and [d] have a higher preference for [edy] than others.

- [ey] also has a high preference for itself

- [in] and [m] also have a preference for [ey] over [edy] (taking into account the number of tokens)

- [in] (however) clearly has a preference for words ending [y] which are neither [edy] or [ey] (apparently [ky, ckhy] are big chunk of the difference)

|

|

|

| Voynich Article in The Atlantic |

|

Posted by: LisaFaginDavis - 08-08-2024, 03:27 PM - Forum: News

- Replies (17)

|

|

Here it is! A very lengthy piece in The Atlantic about my thirty-year friendship with the VMS and new directions for research. Shout-outs to the Team Malta, Claire Bowern, and others:

You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

Enjoy!

|

|

|

| Relations among pattern studies? |

|

Posted by: pfeaster - 08-08-2024, 12:55 PM - Forum: Analysis of the text

- Replies (27)

|

|

Following up on one facet of Voynich Manuscript Day:

(05-08-2024, 08:13 AM)Koen G Wrote: You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.All research was well presented, for example Emma explained statistical concepts well.... But as the data was being presented in the text-focused talks, I felt myself losing the forest through the trees, wondering how things fit into the bigger picture.... I think it would be extremely valuable to the community if someone was able to write an "explain like I'm five" version of these talks, trying to focus on the bigger picture and how Emma's, tavie's and Patrick's findings relate to each other. This might be an assignment even the authors themselves struggle with, but it would be an invaluable exercise. I'm sure I won't be able to do justice to this assignment on my own, but it's interesting enough that I didn't want to leave it unaddressed.

The main thing I think our three presentations shared in common was the goal of searching for structural patterns outside words as earnestly as people have long been searching for structural patterns inside them. We each investigated cases where the actual prevalence of a text element (glyph, word, etc.) turns out to be significantly greater or lesser in a particular context than it "should" be in a random distribution.- In tavie's presentation, we saw that there are many patterns specific to line starts, line ends, and top rows -- more patterns, and stronger ones, than past casual assessments have suggested. Her detection of You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. felt especially new and exciting.

- In Emma's presentation, we saw that there are many patterns in which features of words pair preferentially or dispreferentially with features of adjacent words -- not just word-break combinations (linking the end of one word to the start of the next word), but also pairs of successive beginnings and endings, or words that simply contain particular features anywhere within them. Her introduction of z-scores brings valuable statistical rigor to this type of study.

- In my presentation, I tried to show that treating glyph sequences within words and between words as parts of the same system, rather than analyzing these separately, lets us identify some interesting cyclical patterns that don't necessarily coincide with words as units but do fairly well at "predicting" longer repeating sequences. Here are the slides and script in case anybody wants them:

feaster_vmd_presentation_text.pdf (Size: 113.71 KB / Downloads: 19)

feaster_vmd_presentation_text.pdf (Size: 113.71 KB / Downloads: 19)

feaster_vmd_presentation_slides.pdf (Size: 961.4 KB / Downloads: 22)

feaster_vmd_presentation_slides.pdf (Size: 961.4 KB / Downloads: 22)

Emma and I were both examining features based on their positions relative to other features, and we even identified a few of the same patterns, although from different perspectives and using very different methods. For example, we both identified [dy] as less likely than expected to be followed by [k]:

As I mentioned in Q&A, I've also tried studying higher-order transitional probabilities, such as third-order [dyk>a], which is the same glyph sequence as Emma's [dy.ka], but again, approached from a different perspective and, in that case, broken up differently. Even higher-order transitional probabilities, such as [ydaii>n] or [qokeedy>d], would similarly overlap with some of Emma's start-start and end-end pairings, especially when populated by wild-card characters as in [y***>n] or [q*****>d], except that they'd be defined by an intervening glyph count (with all the attendant uncertainty over what counts as one glyph) rather than by positions within words (with all the attendant uncertainty over word breaks). I sense potential weaknesses in both approaches, but I'm not sure how to get around them.

I assume there's got to be some connection between this type of glyph-by-glyph or word-by-word pattern and the other type of pattern described by tavie, centered on differences by line and paragraph position. After all, for those two types of pattern both to be valid, they must overlap and complement each other, and I even showed a few examples of transitional probabilities that vary strongly by location within lines and paragraphs. But how these two types of patterns interrelate with each other strikes me as still very much a mystery. Do they just coexist? Or do they both result from some other common factor? Or does one level of patterning somehow cause the other level of patterning?

In Q&A, I briefly suggested that the cumulative effect of glyph-by-glyph or word-by-word patterns might be responsible for some kinds of line pattern. If individual glyph-by-glyph or word-by-word patterns of preference are asymmetrical, tending towards certain combinations and away from others, that could perhaps account for some features being unevenly distributed within lines. But I've never been able to demonstrate any such thing statistically, so right now it's no more than an idle guess on my part. Another apparent tendency of certain glyphs to recur preferentially after an interval might account for the greater probability of [p] further along in lines that begin with [p], but it wouldn't offer any insight into the reasons for paragraph-initial [p] itself. (In Emma's analysis, I believe that relationship would translate into a start-anywhere combination.)

Or it could be the other way around. Different paragraph and line positions might cause glyph-by-glyph or word-by-word patterns to vary.

It seems there must be some relationship, but for now, I really don't know what it is, and I'm unsure how to go about trying to find out.

|

|

|

| Summary of Voynich Day presentation on Line Patterns |

|

Posted by: tavie - 08-08-2024, 01:41 AM - Forum: Analysis of the text

- Replies (16)

|

|

I haven't been able to share the slides of the presentation I did at Voynich Day since it is 40 MB. This is because I recorded the audio into the slides themselves so I have to work out how to undo that. I'm also working on how to explain the work better but in the meantime, here's a summary of the presentation.

The aim was about outlining line patterns beyond immediately apparent ones such as gallows usually being the paragraph start initial; p and f appearing mostly on the Top Row; final m being disproportionately at Line End; initial a and ch rarely being at Line Start, etc. Do we see other distinct behaviour in initials and finals (and sometimes word-middle) at Line Start, Line End, and Top Row? Does this vary by scribe or do we see similar trends?

Line Behaviour at Key Positions (Line Start, Line End, Top Row)

My method is rather unsophisticated compared to Emma's; it's just comparing percentages. For the line patterns, firstly I took three large separate chunks for comparison: Herbal A by Lisa's Scribe 1; Balenological by Lisa's Scribe 2; and Stars by Lisa's Scribe 3. This was both to be able to confirm when there is/isn't a cross-scribal tendency but also to reduce distortions in the stats where scribes might cancel each other out, etc.

I also split the text according to its position: for each scribal section, I separated top row words, line start words, line end words, and the "pure middle" (though it does include the bottom row mid-line words) from each other. This was to help spot any "Top Row effects", "Line End effect", etc, and also limit them interfering with each other.

So for example, ch is 24% of middle initials in Herbal A. Ceteris paribus, we'd expect to see it be 24% of LS initials, which would be about 300 ch. We see only 64, so there are over 200 "missing" instances. This makes initial ch "averse" to Line Start.

General issues that could distort/affect statistics include uncertain word breaks (likely especially affecting LE initials); transcription errors; choosing to focus on the scribal level rather than the folio or even smaller level; and my general incompetence.

The three scribes did often show similar tendencies, even if the size of their gaps can vary. Key similarities include for initials:

- At Line Start: all three hate initial ch, and are attracted to initial y, d, s, hence the clusters ych, dch, etc. Simultaneously, all were attracted to /ch/ and /sh/ as word-middle glyphs, and /ai/ and /ee/

- At Line End: All were averse to initial q, ch, and sh.

- At Top Row (middle): All were averse to initial ch and attracted to initial o. Clusters like /opch/ are common.

- At Paragraph End: All were averse to initial q, and prefer initial ch

For finals:

- At Line Start: all three were averse to final y and attracted to final n

- At Line End: all averse to final y and attracted to final m

- At Top Row (middle): all were attracted to final y and averse to final n.

Despite these similarities, there were also some striking differences. The top ones included:

- At Line Start: Scribe 1 in Herbal A is attracted to initial o and q. But Scribe 2 and Scribe 3 are averse to initial o (with some variance in the subclusters), and Scribe 3 in Stars hates initial q

- At Line End: Scribe 1 in Herbal A absolutely loves initial da (as Marco points out, this can reflect Patrick's findings of d becoming more prevalent as you go rightward). Meanwhile, Scribe 2 and Scribe 3 are developing a fondness for rare clusters often beginning with l, r, etc and we see words that are either wholly or mostly exclusive to the Line End position.

- For finals, Scribe 1 in Herbal A really likes final or at Line Start. This isn't a passion particularly shared by the others, but Scribe 3 in Stars is a little attached to final r for Paragraph Start.

I tried some reckless mapping of "missing" glyphs to "surplus" glyphs. I won't reproduce this here. But sometimes there was a vague resemblance between the missing and surplus word types:

- Line Start is the obvious example. We see tons of missing initial ch, and simultaneously tons of surplus word-middle ch in clusters like ych, dch etc.

- Top Row is similar. In its middle, initial ch vanishes, and simultaneously clusters like opch or qopch appear.

These may well be the same word types but the numbers don't always match up, and the finals are often different.

Other times, there is little resemblance between missing word types and surplus word types:

- At Line Start, Scribe 2 and Scribe 3 tend to have large deficits for initial oka/ota/oke/ote words (with some exceptions), and for the q version e.g. initial qoka type words. But we don't see any clear simple surplus word types at Line Start that could be replacing them in sufficient numbers like initial ych etc might replace initial ch. If they are replaced by different word forms with the same meaning, we'd need to look at more creative mutations like initial s or d, which carry large surpluses at Line Start.

- The Line End patterns mentioned above. Scribe 1 in HA's love affair with initial da words, while Scribe 2 and 3 are exploring initial l, r words like "lol"...yet the missing word types don't look very similar and so are hard to match.

"Vertical Impact Effect"

This was based on looking at how often glyphs are immediately under each other at Line Start. On folio 10r, you can see two lines - the 9th and 10th - that both start with o. I call this a "vertical pair" and denote it as o-o.

What's odd is that we rarely see this vertical pair in Scribe 1's Herbal A. It's really odd since Scribe 1 loves starting lines with initial o (and the others hate it). My calculations (hopefully right) were that we should see over 40 o-o vertical pairs. Yet there's this one and...well you can check it out on Voynichese.com.

Simultaneously and suspiciously, we see a similarly sized surplus of o-q vertical pairs.

Scribe 1 in Herbal A really dislikes q-q vertical pairs despite loving q as a Line Start initial. Scribe 2 in Balneological also shows a distaste for q-q. Both show a fondness for q-ch and q-sh, despite ch and sh being averse to Line Starts.

We also see Scribe 1 in Herbal A being attracted to the y-o vertical pairs, and Scribe 2 in Balneological liking d-q vertical pairs. And y in Scribe 3 in Stars seems to like hanging out too much on the bottom row of paragraphs. There were other patterns but those were the ones I thought most worth highlighting.

This seemed really bizarre. It seems the lower glyph in the pair is conditioned on what the upper glyph is. Assuming lines were written in order, that is. Why might it occur?

- Is there an innate anti-duplication sentiment in the scribes where they hate reusing the same glyph immediately below another at Line Start (in the midline, there's more space to play around with)? But we don't see such a marked tendency with y-y or d-d. And s-s actually performs well.

- Is it about space saving or avoiding clashes with the glyphs below (e.g. q-t is messy)? But surely o-o is fine in this regard.

- Is it something to do with a role each glyph plays at Line Start? But what?

More general questions and thoughts

Does it also show scribal awareness, adapting to the circumstances and implied understanding of what they are writing? Or do the strong patterns imply there was a system of rules for them to blindly follow?

I couldn't think of a "natural", e.g. plaintext or linguistic reason for the Vertical Impact behaviour. They may well be at play for the other Line pattern behaviour above but it was hard for me to imagine they could be the main overarching cause.

Could the cause be that the text is meaningless? If meaningless, it doesn't really matter what glyphs are where. But these patterns would require a system with some strong and seemingly arbitrary rules, e.g. "Avoid writing an o directly under another o at Line Start and write a q instead; avoid writing a q under another q and write ch/sh instead, etc"

The same thing would apply if we consider the Line Start initials to be meaningless nulls attached to the real word as part of a cypher hypothesis.

If they are not nulls, are they real? And does that mean the "shorter" word in the midline is an abbreviation, e.g. ychol becomes chol (which as Koen noted is a really weird way to abbreviate)

And lastly as part of the cypher paradigm, if the "mappings" reflect homophones and abbreviations, the apparent interchangeability of glyphs may pose the risk of running out of plaintext letters and making it illegible for even the authorized reader, unless we posit some further internal distinctions or external references.

|

|

|

| Solutions [discussion thread - moved] |

|

Posted by: tavie - 06-08-2024, 10:54 PM - Forum: Voynich Talk

- Replies (58)

|

|

In the wake of Voynich Manuscript Day, I've shared a You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. of all decipherment/language claims that the forum has discussed since its creation. Please do PM me about any missing ones or mistakes. So far we have 51, which is quite remarkable since 2016. I'm guessing the real number of solutions out there beyond the forum must be over a hundred.

It's interesting to count the number of solutions for each language. So far: - Olympic gold medal goes to Latin. We have 15 ones for this, almost 1/3 of the total.

- Trailing in the dust for joint silver are English and Hebrew with 4 each

- And bronze goes to Turkic with three.

Curiously, despite German often being suggested as a candidate language, I haven't yet found a single German solution recorded on the forum.

|

|

|

|

feaster_vmd_presentation_text.pdf (Size: 113.71 KB / Downloads: 19)

feaster_vmd_presentation_text.pdf (Size: 113.71 KB / Downloads: 19)

feaster_vmd_presentation_slides.pdf (Size: 961.4 KB / Downloads: 22)

feaster_vmd_presentation_slides.pdf (Size: 961.4 KB / Downloads: 22)

.

.