| Welcome, Guest |

You have to register before you can post on our site.

|

| Online Users |

There are currently 2052 online users.

» 7 Member(s) | 2043 Guest(s)

Bing, Google, cowcrap, NosDa, R. Sale

|

| Latest Threads |

Elephant in the Room Solu...

Forum: Theories & Solutions

Last Post: MHTamdgidi_(Behrooz)

24 minutes ago

» Replies: 90

» Views: 5,034

|

A random rant about the V...

Forum: Voynich Talk

Last Post: Jorge_Stolfi

37 minutes ago

» Replies: 1

» Views: 72

|

“The Library of Babel” by...

Forum: Fiction, Comics, Films & Videos, Games & other Media

Last Post: ReneZ

2 hours ago

» Replies: 8

» Views: 295

|

Would a NEW Voynich Manus...

Forum: Provenance & history

Last Post: Bluetoes101

2 hours ago

» Replies: 30

» Views: 820

|

On the word "luez" in the...

Forum: Marginalia

Last Post: JoJo_Jost

5 hours ago

» Replies: 7

» Views: 175

|

The Modern Forgery Hypoth...

Forum: Theories & Solutions

Last Post: R. Sale

6 hours ago

» Replies: 381

» Views: 35,384

|

Three arguments in favor ...

Forum: Theories & Solutions

Last Post: JustAnotherTheory

8 hours ago

» Replies: 13

» Views: 832

|

AI-generated "Voynich man...

Forum: Fiction, Comics, Films & Videos, Games & other Media

Last Post: Koen G

11 hours ago

» Replies: 109

» Views: 49,836

|

I found "michiton" in a 1...

Forum: Marginalia

Last Post: JustAnotherTheory

Yesterday, 11:58 AM

» Replies: 4

» Views: 212

|

I've never seen anyone ta...

Forum: Marginalia

Last Post: LisaFaginDavis

15-01-2026, 10:15 PM

» Replies: 3

» Views: 190

|

|

|

| PHONETIC TRANSLATION by AI OF ROMANIZED HEBREW TEXT TO ENGLISH. |

|

Posted by: umbilikal - 12-09-2024, 11:15 PM - Forum: News

- Replies (2)

|

|

I began by directing AI to examine the Romanized text and identifying possible word patterns, repetitions, and contexts. Each segment was carefully analyzed to deduce potential meanings based on context, phonetic resemblance to English words, and thematic consistency across the manuscript. The botanical sections were translated by identifying plant-related words and phrases, while other sections focused on spiritual and esoteric themes. The translations are hypothetical and aim to offer a coherent interpretation based on linguistic patterns and contextual analysis.

I used a version of the manuscript in plain text from here: You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

I built on the hypothesis/assumption brought by Stephen Skinner that the author is Jewish/Italian physician: You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

I instructed AI to treat the text as Romanized Hebrew from circa 600 years ago.

The results AI produced are of course highly hypothetical but, the difference of text segments from the first part of the manuscript differs wildly.

First part:

Translating the Text to English (Interpretive)

Segment Interpretation:

"oy choy koaiin chckhey ol chor"

Hypothetical English: "Prepare the special plant, collect it in the container."

"ykeor chol chol cthol chkor sheol"

Hypothetical English: "Mix the herbs well, dry under the sun."

"olo r okeeol chodaiin okeol tchory"

Hypothetical English: "Combine all roots and place them in the ground."

"ychor cthy cheeky cheo otor oteol"

Hypothetical English: "At this place, mix well with earth and water."

"okcheol chol okeol cthol otcheolom"

Hypothetical English: "Prepare the mixture, let it rest on the ground."

1. tchodairos ar chey qotaiin opchey chtaiir shedy qotor sheol qotody tedy — Could imply 'Upon the entrance, where the winds meet, paths diverge through the ancient oak.'

2. oaiin cheokeeos lkaiin chkal kar cheeody qokeeody qokeey chos ar aiin ol — Might mean 'In the fields of eternity, the spirits dance beneath the starry sky.'

3. y sheol keechey cholkeedy qokaiin chedal lkches ar okain qokaiin oriim — Suggests 'From the sacred grove, the songs echo among the stones of ages.'

4. tchoarorshy qokaiin shey chckhhy sheolkchy qokeol kaiin checkhy ralchs — Could mean 'In the hidden sanctum, whispers weave between the shadows and light.'

5. sain cheeey cheo kcheey qokeey lkeeey okeeey lkchey lchor aiin otain al — Might imply 'The stars speak softly, guiding the steps of the wanderer.'

6. tchedy okeey cheeos lkaiin chey otain cheeody qokeeody okaiin oteedy — Suggests 'At twilight, the voices of old rise with the evening mist.'

7. ykeeol qokaiin olkal airody okaiin okalal loary — Could mean 'Through the archway, the winds carry tales of forgotten journeys.'

8. folorarom otchey qotar air otair opchedy qokeedody cheykeeoy rol lkar chsamoky — Might mean 'From the eastern mountain, the rivers flow, and the forest murmurs of secrets kept.'

9. teoar ain qotar ycheey otaiir otaiin okchy lkchdy oteol ar al araiin okal cheyor — Suggests 'Where paths converge, a lone traveler contemplates the essence of the soul.'

10. sar aiin chotar okeeodar qokain olol olam — Could mean 'Beyond the distant peaks, silence holds the unspoken truth.'

11. fchoctheody keeodar oteedy rchedy qokechy otches oporaiin oteody otaiin otl aroshy — Might imply 'Within the deep wood, the old spirits chant songs of the forgotten.'

12. dcheos otaiin otedy otodaiin qokeey rchchy qeeeear oteedy qokeedy otedar ar t oteesal — Suggests 'In the spaces between moments, knowledge dwells.'

13. tcheolchy lcheol chockhy cheodoiidaiin — Could mean 'In the heart of the forest, dreams grow wild.'

14. fcheshd teody lkeeody oteedy lchealaim shockhol opchedy qotaiin otar ar al oteal — Might imply 'Under the sacred canopy, mysteries unfold beneath the stars.'

15. ycheody qokeeor choltar olkam chokam odal sheckhy qokchedy otor otar toky — Suggests 'The path to wisdom lies in the courage to explore the unknown.'

16. dair ar okaiin chokaiin checkhol cholkaiin olchy — Could mean 'Where light meets shadow, unity is found.'

17. polaiin oteol otedy ar ar al kedy qokeedy olar aiin kchey dal otor ar opchey ro — Might imply 'Beneath the ancient sky, paths intertwine, forming new beginnings.'

18. or sheor oteeo cheey olkeey otol chotair otar qotar okar oko lkedal ram — Suggests 'Where the heavens touch the earth, life flourishes and renews.'

19. solchedy otsheody arl olchey oror — Could mean 'Within the walls of the old city, echoes never fade.'

20. poraiin otar ar okol shedy qokchedy otchdy qotor qoteedar roral fchee llor — Might imply 'Through the winding roads, voices speak of ages past.'

21. dar al sheey qotaiin chor cthol okeshos olchedy qokaiin okal okaiin olo — Suggests 'At the crossroads, the silence of the stones holds countless stories.'

22. ar ar okeey oeky otcheedaiin ol tchdy pcheol kcheor raiin cheey qokaram — Could mean 'Among the echoes of time, wisdom waits patiently.'

23. daiin chl lkeey lkaiin chdain qokain sheor okalchedy qokar olkam ar — Might imply 'From the gathering place of light, paths spread in all directions.'

24. saraiin shedy lcheey olkar okaiin cthor oraiin yteeeor — Suggests 'Under the canopy of stars, truths become clear.'

25. pychdar chckhedy otshedy tcheepchey lky lkches qokody lkeshdy fchocthar opam — Could mean 'With each breath, the winds carry the prayers of the living and the dead.'

I am not a scholar but I do believe AI will be instrumental in solving the manuscript. If indeed it can be solved.

I uploaded text in segments due to AI crashing if the volume of letters were to high so this documents is quite lengthy and repetitious at times.

I previously attempted to direct AI on the assumption that the text was Old Norse mixed with Old English but got no real results.

You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

|

|

|

| MSI at last! |

|

Posted by: LisaFaginDavis - 08-09-2024, 05:47 PM - Forum: News

- Replies (93)

|

|

My friends, I have some very exciting news for you! Roger Easton, who took the MSI images of selected pages of the VMS back in 2014, has sent me the images and given me permission to make them public. You can find them all, including the raw 16-bit TIFFs, here:

You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

I've written a lengthy blogpost with my own initial thoughts about some of these images:

You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

A few important revelations:

1) On f. 1r, the MSI images make the alphabets in the righthand margin legible. There are THREE columns of alphabets, and Rene and I have identified the hand as Marci's! Much more on this in the blog...

2) Those of you working on the inscriptions on f. 17r and 116v will find these images VERY useful!

3) These images make a very strong proof-of-concept case for imaging the entire manuscript. I'm working on it!

4) Dig in! There is much to see and explore!

|

|

|

| Why not positional variation? |

|

Posted by: Koen G - 06-09-2024, 03:30 PM - Forum: Analysis of the text

- Replies (69)

|

|

Whenever I look at the nitty-gritty of Voynichese text, I can't help but feel like some glyphs should be (positional) variants of each other.

* final glyphs have a flourish: Eva- s, n

* In a series of i-minims, the last one looks like EVA-n

* In a series of c-shapes, the last one looks like EVA-s

* EVA-q could be the preferred shape of EVA-y before o

There are also other things, like if you have a series of minims that is not preceded by [o], the first one looks like EVA-a. And I'm sure there's much more like this.

I'm also sure all of this has been remarked many times before. What I don't understand is that some of these features (like [n] being just another minim) have not been adopted as the default approach yet...

|

|

|

| Variation of glyph forms within single pages |

|

Posted by: pfeaster - 24-08-2024, 09:05 PM - Forum: Analysis of the text

- Replies (26)

|

|

I thought I should probably start a new thread to build on the discussion You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view., since I don't want to take over the thread about the recent Atlantic article.

I've been taking a closer look at the formal characteristics Lisa uses in You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. to define each of the five distinct hands she has identified. Among other things, I was curious to see how her classifications might fit in with an impression I have that the bifolio containing f1 and f8 was written by someone who was just figuring out how to use the script for the first time -- especially the first part of f1r, where the second, third, and fourth glyphs strike me as a first attempt to form [a], [ch], and [y], before the writer has quite settled on the stable forms they ended up having. If something as basic as that was still unresolved, I wondered whether the characteristics Lisa used to identify the five distinctive hands might likewise have been in flux at the time when that particular bifolio was written.

Expressed in EVA terms, the characteristics Lisa cites as defining different hands involve the forms of [k] and [n].

For [k], the main distinctive features are:

1. "a sharp angle at the top of the first vertical as the quill changes direction, a bowed crossbar, a round loop, and a very slight foot at the base of the second vertical."

2. "a horizontal, straight crossbar, an oval loop, and an upwardly angled final tick."

3. "similar to that of Scribe 1, although slightly more compact."

4. "a perpendicular crossbar, an oversize loop, and a prominent final foot."

5. "tall and narrow, with a bowed cross-stroke that begins at the top of the vertical, and a minuscule tick at the foot of the second vertical."

So the questions we need to ask about the form of [k] when trying to identify a piece of Voynichese writing with a given hand are:

a. Is the cross-bar bowed or straight?

b. How and where does the cross-bar connect to the first vertical?

c. Is the loop round or oval?

d. How large is the foot on the second vertical, and what form does it take?

e. Is the glyph as a whole unusually compact, or is it unusually tall and narrow?

The tokens of [k] on You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. appear to my eye to alternate indiscriminately among all these options. The cross-bar seems to have about a fifty-fifty chance of being straight or bowed, for example, though this would be hard to quantify in any rigorous way. Loops are variously circles or ovals with their narrow axes horizontal, vertical, or diagonal.

For [n], the definitive characteristics are:

1. "conclude with a backward flourish that stretches as far as the penultimate minim."

2. "final backstroke...is short, barely passing the final minim."

3. "final stroke...curves back on itself, nearly touching the top of the final minim."

4. "final stroke...is tall, with only a slight curvature."

5. "has a long, low finial that finishes above the penultimate minim."

The tokens of [n] on You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. are mostly of type 1, but with several cases that appear closer to type 3 and several others that appear closer to type 5:

On You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. (adjacent to You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. on the same side of the bifolio), [k] varies similarly, including the mix of bowed and straight cross-bars:

Meanwhile, [n] is again mostly of type 1, but with one very convincing example of type 3 (third in top row):

On f8r, [k] again varies --

-- while [n] is again mostly type 1, but with one very convincing example of type 5 (second in second row):

On f1v, [k] varies yet again:

There aren't many tokens of [n], but what there is looks plausibly like type 1.

So for what it's worth, it looks to me as though when f1 and f8 were written, the writer was alternating haphazardly between the various forms of [k], and favored the form of [n] associated with hand 1 but was also quite capable of producing the forms associated with hands 3 and 5. What do others see?

|

|

|

| Binomial distribution in VMS |

|

Posted by: bi3mw - 17-08-2024, 12:33 AM - Forum: Analysis of the text

- Replies (67)

|

|

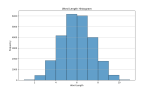

Question: What if the words in the VMS have been shortened or expanded with fill characters (here X) so that they end up corresponding to a binomial distribution (with whatever system)?

Here is a line from a comparative text ( regimen sanitatis ):

Input example:

Capitulum primum De regulis sumptis ex parte elementorum nostro corpori occurrentium ab extra

Output example:

Ca primum DeXXXXX regul sump exXXXX parteX elemento nost corpo occu abXXXX extra

Distribution in the entire, modified text ( regimen sanitatis ):

Code: import sys

import numpy as np

from scipy.special import comb

def calculate_binomial_distribution(n, max_length):

"""Berechnet eine Binomialverteilung für Wortlängen."""

k_values = np.arange(1, max_length + 1)

# Berechne die Binomialverteilung für die Formel choose(9, k-1) / 2^9

probabilities = [comb(n, k-1) / (2 ** n) for k in k_values]

# Normiere die Verteilung

probabilities /= np.sum(probabilities)

return probabilities

def adjust_word_lengths(words, target_distribution):

"""Passt die Wortlängen an die Zielverteilung an, indem Wörter gekürzt oder verlängert werden."""

adjusted_words = []

max_word_length = len(target_distribution)

length_bins = np.arange(1, max_word_length + 1)

length_probs = np.array(target_distribution)

for word in words:

current_length = len(word)

target_length = np.random.choice(length_bins, p=length_probs)

# Falls die Zielwortlänge kleiner ist, kürze das Wort

if target_length < current_length:

adjusted_words.append(word[:target_length])

# Falls die Zielwortlänge größer ist, verlängere das Wort mit 'X'

elif target_length > current_length:

adjusted_words.append(word + 'X' * (target_length - current_length))

else:

adjusted_words.append(word) # Wenn die Länge passt, bleibt das Wort unverändert

return adjusted_words

def process_text(file_path):

"""Liest den Text aus der Datei, passt die Wortlängen an und gibt den neuen Text zurück."""

try:

with open(file_path, 'r', encoding='utf-8') as file:

lines = file.readlines()

except FileNotFoundError:

print(f"Error: The file {file_path} was not found.")

sys.exit(1)

except IOError as e:

print(f"Error: An error occurred while reading the file: {e}")

sys.exit(1)

max_word_length = 15 # Maximale Wortlänge festlegen

n = 9 # Anzahl der Würfe für die Binomialverteilung

# Berechne die Binomialverteilung

target_distribution = calculate_binomial_distribution(n, max_word_length)

adjusted_lines = []

for line in lines:

words = line.split()

adjusted_words = adjust_word_lengths(words, target_distribution)

adjusted_lines.append(' '.join(adjusted_words))

return '\n'.join(adjusted_lines)

def main():

if len(sys.argv) != 2:

print("Usage: python adjust_word_length.py <filename>")

sys.exit(1)

file_path = sys.argv[1]

new_text = process_text(file_path)

print("Modified text:")

print(new_text)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Quote:ChatGPT

One could design a volvelle that aims to change the word lengths of a text according to a specific distribution. This could be done through the use of rotating disks, each giving specific instructions on how words should be edited.

Example of a volvelle for word length manipulation

Here is a hypothetical description of what a volvelle could look like for this task:

Circle 1: Defines the possible word lengths from 1 to 15 (depending on the maximum word length).

Circle 2: Gives the probability for each word length based on a certain distribution (e.g. binomial distribution).

Circle 3: Instructions for shortening or expanding words to achieve the target distribution.

Use of a volvelle

1. user enters the text.

2. volvelle is rotated to obtain the rules for shortening or expanding words.

3. instructions are applied to the text.

|

|

|

| Argent et Azure |

|

Posted by: R. Sale - 14-08-2024, 08:48 PM - Forum: Imagery

- Replies (7)

|

|

Argent et azure, how long has it been? Azure is blue and argent is silver, which is also white, which is nothing. No pigment application is needed to represent an argent tincture.

In Koen's recent presentation "Too blue?" there is clear evidence of the extraordinary prevalence of blue paint in the VMs. Furthermore, there is the most interesting excessive presence of "white". Blue and white, what can it mean? Blue and white on the alternating petals of the flowers, what can it mean? Alternating blue and [tricky] camo stripes on the tubs of White Aries, what can it mean? Pick your interpretation. How about heraldry? Armorial and ecclesiastical heraldry combined with the history of the Fieschi popes. Does the investigator know the armorial blazon of the pope who initiated the tradition of the cardinal's red galero?

Why is the VMs so blue? In part perhaps, it is an effort to create a sort of sensory 'overload' for the presence of items that have been painted blue. You see so many that you get tired of looking at them. If the heraldic interpretation of blue stripes is to be valid, then the stripes *must* be blue. However, if the selected usage of blue paint is (near) unique, then identification will be more obvious. So, blue paint is found in numerous places.

VMs White Aries is by far the most carefully painted page in the Zodiac sequence, with plenty of color on the nymphs and their tubs. Plenty of blue to distract from the blue stripes. And all this thorough application of color also tends to emphasize the "whiteness" of White Aries.

In addition, there is the intentional association of the Fieschi popes specifically with the "White Aries" medallion, in that the popes and the white sacrificial animal were perceived to have celestial connections. This is one of several structural confirmations built into this illustration.

|

|

|

|