| Welcome, Guest |

You have to register before you can post on our site.

|

| Latest Threads |

The Book Switch Theory

Forum: Theories & Solutions

Last Post: Jorge_Stolfi

1 hour ago

» Replies: 131

» Views: 6,689

|

Can we go further?

Forum: Analysis of the text

Last Post: Battler

1 hour ago

» Replies: 23

» Views: 753

|

No text, but a visual cod...

Forum: Theories & Solutions

Last Post: Antonio García Jiménez

2 hours ago

» Replies: 1,688

» Views: 1,036,827

|

The origin of Fabrizio Sa...

Forum: Imagery

Last Post: Fabrizio Salani

3 hours ago

» Replies: 4

» Views: 207

|

The claimed Voynich page

Forum: Imagery

Last Post: Fabrizio Salani

4 hours ago

» Replies: 85

» Views: 13,409

|

f17r multispectral images

Forum: Marginalia

Last Post: Bernd

4 hours ago

» Replies: 114

» Views: 44,127

|

Why and how the text coul...

Forum: Theories & Solutions

Last Post: JoJo_Jost

5 hours ago

» Replies: 87

» Views: 8,099

|

Voynich Marijuana Plant D...

Forum: Analysis of the text

Last Post: Bluetoes101

11 hours ago

» Replies: 5

» Views: 339

|

Voynich Zoom CFP

Forum: News

Last Post: ReneZ

Today, 12:48 AM

» Replies: 31

» Views: 3,054

|

How fast could a scribe w...

Forum: Analysis of the text

Last Post: dexdex

Yesterday, 11:41 PM

» Replies: 27

» Views: 497

|

|

|

| An inference of the species of the plant on f3r |

|

Posted by: JonathanZhang0813 - 14-11-2025, 02:49 PM - Forum: Imagery

- Replies (3)

|

|

Hi! My name is Jonathan Zhang, and I come from Shanghai, China. I was born on August 13, 2010 (yes, I'm just fifteen years old). I'm very interested in the Voynich Manuscript.

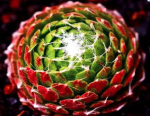

In discussion of the plant that appeared on page f3r, I've got an inference (or theory) of its species. It might have been the Sempervivum.

Sempervivum is a genus within the family Crassulaceae.

The most typical form of Sempervivum is a ground-hugging, flower-like rosette. Although it is short, when it blooms, the plant sends up a single, upright, unbranched flower stalk from the center of the rosette.

Its leaves are arranged in a tight spiral, layered upon each other, forming a very regular shape that looks like a pagoda or a rose.

Many Sempervivum varieties have leaf tips or margins adorned with white, cobweb-like "threads" or cartilaginous edges. A notable example is Sempervivum arachnoideum (Cobweb Houseleek), whose leaf tips produce white, silk-like hairs that cover the rosette like a spider's web, giving it a white-edged appearance.

The hairs, glandular dots, or color variations on the leaves can, in specific varieties and under certain conditions, create a texture similar to "spots."

Sempervivums' color changes with the seasons, light exposure, and temperature variations. In environments with ample sunlight and significant temperature differences (especially in autumn and winter), the leaves can turn from green to bright red, purple, or reddish-brown.

As alpine succulents, they possess short, dense fibrous root systems, an adaptation to shallow soils like rock crevices.

Sempervivum species are native to mountainous regions of Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East.

The Roman scholar Pliny the Elder recorded its uses in his Natural History. In medieval Europe, the plant was believed to counteract poison and treat earaches, insect bites, and skin problems. Its sap was sometimes used as an anti-inflammatory agent.

And by the way, I also noticed an interesting fact. The word "Sempervivum" can be separated into two Latin words—"Semper" (which means "forever") and "vivum" (which means "life"). connecting together, which means "immortality."

Actually, the Sempervivum does not look like the plant displayed on page f3r…… The leaves of the plant displayed on You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. are growing opposite or whorled. The leaves of Sempervivum grow rosulate or fascicled.

So there is a closer "guess" concerning the leaf patterns. It might be the Sedum Rupestre.

|

|

|

Korean Solution

Korean Solution |

|

Posted by: rikforto - 13-11-2025, 07:36 PM - Forum: Theories & Solutions

- Replies (14)

|

|

Voynich enthusiasts! The VMS has vexed and befuddled scholars for nearly a century, but I believe after 90 minutes of working on the problem that the answer was in front of us all along: It is a phonetic rendering of a Middle Korean alchemical text, written by a mysterious Lee Si-eun. From the introduction, we can see that it deals with the transformation of the spirit and other alchemical concepts.

Note: You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view., but an answer to the frequent question, "How likely is it that I failed to solve the manuscript since I got a translation?" The answer, for those who do not wish to read through the entire "solution" here, is it that is it is very likely, as in about an hour and a half plus write-up time I was able to get an alchemical-sounding translation, complete with poetic language and the author's own signature. The Korean here is mostly nonsense---and I apologize to any Korean speaker reading it for my crimes against your language---but with some very light massaging I was able to get a wonderfully "poetic" English rendering. I am hardly the first person to do this, with the You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. being probably the most widely discussed example of a good faith version of this genre, but hopefully the notes here in Italics will answer why it seems quite likely that a would-be solver found a translation even if the solution is wrong, and why the mere fact of having a translation is less impressive than it looks. And if you're wondering why I went to all this trouble, besides getting a bee in my bonnet about this argument, it did actually help me see Voynichese in a new light and how very malleable the text is if you're not careful and that was instructive for me.

The key to seeing this is noticing the similarity to Korean linguistic features. Just as Voynich has 3 kinds of vowels, a o and y, Korean has 3 kinds of vowels, light (ㅏ and ㅗ), dark (ㅓ and ㅜ), and neutral (ㅡ and ㅣ).

Note: This is an extraordinary amount of freedom, and even more than it looks. There are several combined vowels for each category, meaning that if I did not like a translation, I could just keep changing vowels until Papago---we'll get there---gave me something semi-coherent. The half explanation, leaving out ㅐ, ㅔ, ㅞ, ㅝ, ㅒ, ㅕ, ㅛ, ㅠ, and probably a few others is extremely typical of this sort of announcement, and you'll save yourself some grief checking for it.

Likewise, just as there are 14 basic Voynich Letters, there are 14 basic Korean consonants.

k ㅈ

f ㅂ

t ㅅ

p ㄷ

ch ㄱ

d ㅇ

e ㅁ

g ㄹ

l ㄴ

m ㅋ

q ㅎ

r ㅌ

s ㅊ

h ㅍ

The bench letters represent the doubling of consonants that are typical in Korean, with sh representing ㅉ.

Note: Typical of this sort of "solution", I have no explanation for why these correspondences are the way they are, which is also a problem with how the vowels match a particular EVA letter as well. But if you can get past that large problem, this does not provide any degrees of freedom, so while I left myself plenty in the vowels, I would like some credit for not overloading the system even further at this point.

The other key to recognizing the Korean nature of the text is to see the various particles and verb endings from the text:

aiin 은/는

ain 을/를

air 하고

aiir 이/가

al 고

ar 서

an 의

or 면

ol 이나/나

oiin 로/으로

os 도

y 습니다/ㅂ니다

Note: Why are these lined up this way? Well, like I say, you just have to see! Joking aside, I did have some strategy with spacing and frequency that I can explain if anyone really wants the details, but mostly I just slapped them down in my notebook while yelling YOLO. There are no degrees of freedom here when rendering the Voynichese into Korean, but two features of Korean probably gave me some wiggle room in the machine translation. The pairs 은/는, etc. are phonetic alternates, so I could choose them based on the rest of the word; in 1400 they were actually written down in Chinese characters without phonetic variation, so I could defend this choice in a sincere proposal, though, obviously, this isn't that. Likewise, several of these can be both noun and verb endings, albeit with different meanings, giving a less clear signal to a machine which part of speech their attached root belongs to. This too is a real feature of Korean that occasionally trips up both human and machine readers, so it is perfectly valid, at least if you accept my table handed down from on high.

With this in hand, we are able to translate the first paragraph of the manuscript:

Fachys ykal ar ataiin shol shor cthres ykal sholdy

Shory ckhar ory kair chtaiin shar ars cthar cthar dan

Syaiir sheky or ykaiin shol cthoary cthor daraiin sa

Ooiin oteey oreos roloty cthar daiin otaiin or okan

Dairy chear cthaiin cphar cfhaiin ydaraishy

bogiteu ojjigo aeching yaesineun kkina kkeumyon sseuchimit ijjigo kkingneungseumnida kkeungchiseumnida jjiso icheuseumnida jjihago giseun kkeuso achiteu sseuso sseuso ie tiga kkeummijjiseumnida myon ojjeuneun kkeuina ssoachiseumnida sseumyon achineun ta oro onmimeuseumnida ocheumeudo jonosiseumnida sseuso ineun isieun myon ojjeue aichiseumnida gimeuso sineun tteuso ppeuneun euaechoga kkeumnida

보기트 어찌고 애칭 얘시는 끼나 끄면 쓰치밑 이찌고 낑능습니다.

끙치습니다.

찌서 이츠습니다.

찌하고 깃은 끄서 아치트 쓰서 쓰서 이의 티가 끔미찌습니다.

면 어쯔는 끄이나 써아치습니다

쓰면 아치는 타 어로 엇미므습니다.

어츠므도 저너시습니다.

쓰서 이는 이시은 면 어쯔의 아이치습니다.

기므서 시는 뜨서 쁘는 으애초가 끕니다.

Note: I gave it away already, but the main tricks here are that all those vowels are basically arbitrarily chosen and the Korean is gibberish, though I'm going to stick to the bit and call it "poetic". Unlike a lot of these translations, however, the sentence breaks are as principled as the verb endings (though, see above for how principled they really are) because Korean has regular, pronounced finite verb endings and matrix verbs are sentence final, sentence endings are never ambiguous. Most solutions require a better explanation for how the text was broken up, though I should not leave it implied in my explanation here.

The Korean is rather poetic and non-standard, but using Papago, a popular Korean to English translator maintained by Naver in South Korea, and Chat-GPT, I was able to arrive at the following poetic translation:

If you turn off your perception, you'll gain weight under your teeth and whine.

It is moaning.

It is steaming.

When the essence (깃, spirit) cools or is turned off, the body or teeth (symbol of speech/expression) grow distorted or heavy.

Then what? One must either turn it off or use it.

If you use it, the arch doesn't go well with the other word

So it is, so it is.

I'm Lee Si Eun, pen name "Eoohoo", who wrote this.

So the poem is hot and I'm going to end it.

Note: It is certainly steaming! There is no poetic tradition even identified here, even though I was encouraged to see it that way by Chat-GPT, and while my Korean is not good enough to render a final judgement, I know enough about how this was created to say that Chat-GPT is, politely, offering me some bovine fecal matter. (I did rely on it only for the translation, but it volunteered a bunch of analysis that colored some of my choices as I edited Papago's much rougher first pass. I will not argue if this gets thrown in the AI trash pile, not least of all because the solution is not in good faith and I'm not attached to it, but I really did try to stay well on this side of an AI solution.) The machine translators' main goal is to output a text, and so it covered up a bunch of problems in the underlying Korean for me, making this entire exercise alarmingly smooth; I thought I was going to have to push a bit harder to get a translation!

There are several important observations to be gleaned from this. Perhaps most importantly, we have recovered the author's name, as well as a pen name. Hopefully we are able to identify his work from elsewhere, or perhaps we have identified a new scholar of Korean alchemy. The emphasis on teeth is interesting, perhaps symbolizing the way the written word can lead someone to alchemical enlightenment. The importance of heating and cooling, long known to be a key part of alchemy, is also suggestive. Trying to keep the male body hot with Yang energy would be an important goal of any Korean alchemist, and we see here that cooling may lead to the speech and body becoming heavy. However, at the end, we see that the alchemist is also worried about too much heat, which in traditional Korean thinking could lead to a melting of metal (金) energy and must be tempered. This duality between hot and cold reflects yang and yin, and is likely to be the subject of the rest of the text. Further translation and study is needed to unlock the rest of the secrets.

Note: All this speculation is original, and though grounded in actual things I know about traditional Korean medicine, I am just spinning a tale based on an English "poem" extracted from nonsense Korean. It is worth exactly that much.

I am sure I will face a good deal of criticism for this, as Voynich enthusiasts are very harsh towards solvers. But I would ask: How likely is it that I correctly found alchemical ideas about the spirit, heating, and the special significance of teeth? How likely is it that I identified the author? Does the fact that it references a poem seem like a coincidence? And all this in just an hour and a half of work!

Note: As is hopefully apparent at this point, a few degrees of freedom of some elbow grease on the translation and you will end up with some writing on alchemy. This doesn't disprove your solution, of course, but the fact of having a translation is much less impressive than it might seem if you have not been around the manuscript very long. The fact that I was able to add to that crowded field so quickly---you'll have to take my word that it was about 90 minutes to get this system---and could probably plug a few holes with a bit more work shows how easy it is to get the manuscript to give up some alchemy if you want it too. The biggest thing I've not addressed with this example is volume of translation, but I think it's clear I could scale this if I was willing to spend the time, which I'm not; the relative ease of getting the first paragraph is very much repeatable because it relies on the feature of machine translation that it always outputs meaningful text by design. Manipulating the vowels is a little tedious, but I could continue to torture Korean until Papago screams in something resembling alchemical English. All in all, it is almost a given that someone proposing a solution has found something in their translation that hints to it being correct, as it happens quite frequently.

A final observation for people who have been directed here because they think it is unlikely they got a translation by chance: People usually fall back on this when their arguments about their translations are not going over well. Hopefully I've shown that it is a dead end to rely on the existence of an English translation to carry you through and would ask if you see your work in my example here: Do the correspondences come out of nowhere (at least as you've explained them)? Are they a simple substitution, which will not allow a translation of any text because of You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.? Are there choices being made creating degrees of freedom that you have not justified? Is the underlying language poetic at best, and garbled at worst? Are you overly relying on translation and English gloss, either human or machine, to smooth that out? Nearly 100% of translations to date have been from some combination of arbitrary sound assignment giving degrees of freedom and further massaging when rendering the final interpretation of the text---and so that likelihood is that statistical prior that your arguments must overcome.

To everyone else: I will answer inquiries about my method here provided they are in the spirit that I think this approach is a wretched failure. If you want the full experience of discussing a novel solution in 2025, I can direct you to a scattered and incomplete accounting on a website ill-suited to actually making an argument for my methodology and a bunch of forthcoming TikTok and YouTube videos, but unfortunately I am not so committed to the bit to have actually created them so you'll have to play along. But in all seriousness, if you're curious about the inner-workings of how I made this pastiche, ask away!

|

|

|

| f72v1 - Crown style |

|

Posted by: Bluetoes101 - 12-11-2025, 11:43 PM - Forum: Imagery

- Replies (7)

|

|

"When do we first see this sort of crown?"

The crown is defined by two parts,

- The "zigzag" lower section referred to as a "eastern/ancient crown".

- The arch above, topped with a cross - Imperial/Christian symbolism.

This combination of the two parts might be traced to Rudolf IV (House of Habsburg).

Rudolf IV wanted to create a new rank, the "Archduke" (archidux). To do this he forged documents, and commissioned likenesses of himself as the "Archduke" in the "Archducal hat" to support the claim. The combination of the two styles of the archducal hat is thought to be unique for the time and that Rudolf may have got the idea for the lower part from old coins. Rudolf was (self appointed) Archduke 1358-1365, the image is thought to be 1360-1365, the Archducal hat is thought to be a fabrication. The artist had some issues with the arch, but otherwise is meant to be a true to life depiction. The eyes are due to facial palsy, the choice to include this might speak to the authenticity the image was meant to show.

1359–1363 (Obviously now very worn)

With the imperial crown lost to the Habsburgs due to the assassination of Rudolf's grandfather and the Habsburgs being left out of the order of the golden bull by Emperor Charles IV.

It is not hard to see what the aim of this new insignia Rudolf had created was, by hook or by crook he wanted to raise his perceived importance on the political map.

There are also other signs of this in below quote from WIKI, also his want to not be outdone by Charles IV.

"Rudolf extended St. Stephen's Cathedral, with the construction of its gothic nave being started under Rudolf's rule. The construction efforts can be seen as an attempt to compete with St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague.

Rudolf had himself and his wife depicted on a cenotaph at the cathedral's entrance. Similarly, by founding the University of Vienna in 1365, Rudolf sought to match Charles IV's founding of the Charles University of Prague in 1348.

Still known as Alma Mater Rudolphina today, the University of Vienna is the oldest continuously operating university in the German-speaking world. However, a faculty of theology, which was considered crucial for a university at that time,

was not established until 1385, twenty years after Rudolf's death."

Once Rudolf's documents were found to be forgeries by Charles IV, he was commanded to stop using the insignias and titles he created for himself, the response seems to have been "yeah, whatever.." as he didn't stop and continued to make more. A few years later Rudolf seems to have been paranoid with his imminent death (in his early 20's), then he died suddenly in Milan. Eventually the fruits of Rudolf's labours were realised however when "Ernest I" declared himself "Archduke" in 1414 and had an archducal hat made.

Later on Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor (House of Habsburg) and Archduke of Austria 1457–1493 decided to instate all the powers granted by the forged documents and lay the foundations for the Habsburg monarchy.

Rudolf's story is an interesting read. Points I touched on here as well as some details on the forged documents can be found here - You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

As some may know he is thought to be responsible for a cipher - You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

I just wanted to touch on some of the history as I think it shows that this insignia was not "some random crown design", but one with a purpose and historical relevance.

This is not to say the VM crown is this crown, but the design seems to originate with Rudolf and the years 1358-1365.

An issue may be the lack of details on the arch, however this image from Zbraslav Chronicle (14C) shows,

Top left - You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

Top centre - You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

Top right - You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

Bottom left - You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

Bottom centre - You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

Bottom right - You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

As you can see all the arch's are plain with a cross on top.

Charles IV - Top right, has his crowns displayed here - You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

none of them have a plain arch, so the drawer decided to omit details or they just had an "imperial crown" that they drew (seems more likely).

It might be the VM drawer also drew a "crown" and added the arch and cross on top and the zig-zag design + arch is not based on anything we can pull any meaning from.

.. but that's not as fun to speculate about!

Here are some other images of later Archdukes of Austria (House of Habsburg) that I thought showed a similar style.

Sigismund, Archduke of Austria 1477-1496

"A half guldengroschen from 1484."

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, Archduke of Austria 1519–1521

Created: 1521

Some that we still have

A newer statue of Rudolf - 1885

|

|

|

| The half-arcaded pool - f78v |

|

Posted by: R. Sale - 12-11-2025, 08:46 PM - Forum: Imagery

- Replies (5)

|

|

VMs You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. is the mystery of the half-arcaded pool. As part of the balneological section, the centrally placed illustration shows another group of women in a green pool. That's something which this section of the VMs depicts, the different groupings of nude female figures in green or blue pools.

The question here concerns the pattern that is found on the left-hand portion of the tub wall on f78v. A series of several rounded arches that the so-called "ignorant" artist has absent-mindedly painted blue. There is no other example of a patterned tub in this section. To discover that these arches might be interpreted as blue windows is slightly amusing. The pattern is "arcaded", and the tub is only half patterned, only on the secondary portion, you might say. That is the intentional creation of ambiguity - where this claim is not unique to this example but occurs in other VMs illustrations.

Not only is this patterned tub a unique occurrence, the number of women in this tub is nine and there is no other tub in the VMs balneological section with nine occupants. The number nine may prompt the speculation that these women might represent the classical Muses in their mythic pool.

Here is another example, like the cosmic comparison, where history provides quite an interesting example. Harley 4431

You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

Nine Muses in an arcaded fountain in an illustration with good historical provenance: Paris, 1410-1414. There are a few other versions of the Muses, but not in an arcaded pool.

Of course, the provenance of BNF Fr. 565 is Paris c. 1410. So, the You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. illustration is another independent element with a chronological match to the other VMs indicators of 15th Century information.

|

|

|

| On the character of Wilfrid Voynich |

|

Posted by: ReneZ - 12-11-2025, 04:23 AM - Forum: Provenance & history

- Replies (26)

|

|

Both in the "Voynich faked it" thread and the "Voynich MS book swap" thread, statements or assumptions are made about Voynich's character - his reliability and his truthfulness. Both theories rely heavily on the assumption that Voynich should not be trusted at all, which may be a bit harsh.

Now here, I don't want to go into the aspects of how his character affects these two theories. There are already threads about that, and such aspects can be continued there. If this diverges into these directions, it can be closed. What I want to do here is look both at the evidence we have for Voynich's character, and the high level of subjectivity in this entire topic.

This quote is a good starting point:

(11-11-2025, 06:17 PM)proto57 Wrote: You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.[...] the description of Voynich, by G. Orioli, to Antonio. [...] Of course Orioli got Voynich's religion incorrect, and also, it sounds somewhat bigoted on his part... but here it is:

"As to Voynich--he was a Polish Jew, a bent kind of creature and getting

on for sixty. I liked his shop in Shaftesbury Avenue; it was full of books

and well kept, and Voynich himself was most obliging to me. He gave me one

of his excellent catalogues to study, begging me to note the prices: 'Always

keep the price as high as possible, if you ever have a book to sell,' he

added. Then in a squeaky voice and in an accent which I even then recognized

as not being English he told me that he had bought a bookshop in Florence

called the 'Libreria Franceschini.'"

"'I know that shop,' I said."

"'Well, it is full of incunabula. Absolutely crammed with incunabula.'"

"'Surely a bookshop ought to be full of books?'"

"He laughed heartily at my ignorance, explained what incunabula were, and

went on in his enthusiastic fashion:"

"'Millions of books, shelves and shelves of the greatest rarities in the

world. What I have discovered in Italy is altogether unbelievable! Just

listen to this. I once went to a convent and the monks showed me their

library. It was a mine of early printed books and codexes and illuminated

manuscripts. I nearly fainted--I assure you I nearly fainted on the spot.

But I managed to keep my head all the same, and told the monks they could

have a most interesting and valuable collection of modern theological works

to replace that dusty rubbish. I succeeded in persuading the Father

Superior, and in a month that whole library was in my hands, and I sent them

a cartload of modern trash in exchange. Now take my advice: drop your

present job and become a bookseller.'"

Now there is a bit of "all booksellers are liars, said a bookseller" in this.

This is not trying to be smart, but shows how easy it is, on such a subjective topic, to trust the things one wants to believe, and to distrust what one does not want to believe.

This is so easy, that it may not even be done consciously.

To be very specific:

should we doubt that Voynich discovered a faded signature on the first folio of the MS?

yet at the same time:

take literally that he exchanged valuable old books for a cartload of modern trash?

(Sounds like bragging to me).

Should we trust Orioli?

Voynich was not Jewish, not near his sixties (he was 47 in 1912) and he was described by others quite differently from a bent creature.

Here is my attempt at a biography of Voynich: You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

which suffers in some areas from the same unreliability of evidence.

The best description of Voynich's person is the quoted chapter by E.Millicent Sowerby, which I can thoroughly recommend. It brings him to life.

One has to recognise when she repeats exaggerated stories by Voynich of his earlier life though.

She takes very strong issue with Orioli's description of Voynich, and quotes how Voynich's wife descibed him as having the head and shoulders of a 'Norwegian god'.

I also quote a statement from one of Voynich's Polish friends, found by Rafal Prinke:

"He [Wojnicz] had exuberant phantasy and took its results for reality, in which he solemnly believed. Later he became [...] a very practical antiquarian books dealer and made a considerable fortune, which he was always happy to share with anyone. And so in that man lived in agreement incredible phantasy (others call it lies), truly American pragmatism and good heart"

There is also a published obituary by James Westfall Thompson, which is entirely laudatory and we should not consider useful.

PS: minor details in the biography are not up to date anymore, e.g. I also have a copy of Orioli now.

I would appreciate hearing about additional references if known.

|

|

|

| Pareidolia ... on f0v |

|

Posted by: Jorge_Stolfi - 10-11-2025, 07:01 PM - Forum: Imagery

- Replies (1)

|

|

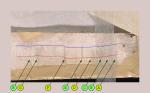

While hallucinating retracings on f1v, I noticed that one of the tendrils (Y below) sprouting from the root of the plant seemed to continue past the edge of the vellum, onto the previous folio, at (A). And there were three other tendrils that seemed to do the sam, at (D,F,G), but less distinctly:

But that "previous folio" would not be any proper folio. It would be "f0v", the verso of the front cover.

Fortunately the BL 2014 scans include an image of that page:

There are indeed a few gray streaks on f0v that coincide with the tendrils (A,D,F,G) of f1v. But there are other streaks there -- notably (E), but also (B,C,H). Going back to f1v, those streaks seem to correspond to very faint additional tendrils (S,T,U) from the root. But you may need a good pareidolioscope to see them.

Some things to note:

- Streaks (F) and (H) on f0v coincide with creases on the material, and may be just that.

- Streaks (A-H) are straight, narrow, vertical, and end at about the same height.

- There are no other similar streaks on f0v. There are several more gray spots, but they are all irregular, broader, and fuzzy.

- The material where those streaks occur seems to be a sheet of white material (paper? vellum?) that was originally glued to the front cover, but eventually was scalped away with a sharp blade, leaving only that strip 10-15 mm wide.

The red line on the image of f0v is where the edge of folio f1 lies on the image of f1v. But the streaks extend upwards beyond that line. The blue line is where the edge of folio f1 should have been, if the streaks are indeed "overflow" from f1v. That line is 60 pixels (~4 mm) above the red line. Could it be that when the binding was renewed, bifolio f1-f8 moved up by 4mm relative to the cover? How much could the edge of f1v move upwards just by variations in the bending of the folio?

There is a bigger and possibly more important mystery on that page, namely the resemblance between that plant and the plant on the southeast corner of f102r1 (Pharma). They are not just the same plant. It must be that one was copied from the other, or both were copied from the same original. If the former, which one was the original, and which one is the copy? The You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. version includes a flower, while the f102r1 doesn't. The tendrils on the root are similar but not identical, and so are the leaves...

All the best, --stolfi

|

|

|

| Exploring a New Angle on the Voynich Manuscript – Gidea Hall / Essex Connection |

|

Posted by: 5dd95 - 09-11-2025, 02:00 PM - Forum: The Slop Bucket

- Replies (18)

|

|

Hello everyone,

I’m researching a potential new perspective on the provenance of the Voynich Manuscript, exploring links to Gidea Hall in Essex and the Cooke family archives. My work draws on primary sources and historical records, some of which have not been widely discussed in Voynich research.

The goal is to invite discussion and feedback from fellow researchers and enthusiasts, particularly on verifying archival links, manuscript details, and historical context.

You can explore the evidence and findings here: You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

A membership portal will be opening soon, offering deeper access to evidence, interactive timelines, and research tools for collaborators.

I’d welcome any thoughts or suggestions!

Best regards,

Edward Earp

|

|

|

| The Book Switch Theory |

|

Posted by: Jorge_Stolfi - 09-11-2025, 09:40 AM - Forum: Theories & Solutions

- Replies (131)

|

|

Hi all, I am creating this thread for a theory that is quite distinct from the Modern Forgery Theory, even though it potentially involves foul play by Voynich.

The Book Switch Theory claims that the VMS that we know, Beinecke MS408, is not the book that is mentioned in Marci's letter (hereinafter called "BookA"). There are two variants of this theory: - H1: When Voynich acquired MS408, Marci's letter was attached to it

- H2: It was Voynich who attached Marci's letter to MS408.

Here are the factual claims pertinent to this theory, which, AFAIK, are supported by good evidence. Because of H2, I do not consider "good" any evidence that depends on anything that Voynich said or wrote, or any material evidence that he could have easily misrepresented, planted, adulterated, or forged.- F1: Rudolf II once bought from Widemann a set of book for 600 ducats. Evidence: accounting records found by Rene and others.

- F2: In the early 1600s, Barschius had a book (BookA) with figures of plants that were not known in Europe, written in a language that no one could identify. He wrote about it to Kircher, with a few sample pages. Kircher did not recognize the language and was intrigued enough to ask for the whole book. Barschius did not send it. When Barschius died, his friend Marci sent BookA to Kircher. Evidence: the letters between Kircher, Barschius, Marci, and others, that mention BookA. (While Voynich could have forged Marci's letter, the ensemble of the letters is strong evidence that it is genuine.)

- F3: Thousands of Kircher's books ended up in various locations in Rome, under control of the Jesuits. Evidence: various catalogs and other records collected by Rene and others.

- F4: In ~1911, Voynich acquired hundred of books from the Jesuits in Rome. Evidence: accounting records of the Jesuits.

- F5: MS408 was written in the 1400s. Evidence: the C14 date for the vellum and all the stylistic and statistical details. It is very unlikely that a forgery by Voynich or someone could have faked those details so well that it evaded all the tests that were developed and used in the last 100 years.

And that seems to be all that we have good evidence for. Factual claims for which we do not have good evidence include:- C0: BookA was ever in possession of Rudolf II

- C1: MS408 was ever in possession of Rudolf II

- C2: Sinapius ever owned MS408.

- C3: BookA was one of the books held by Jesuits by 1911.

- C4: MS408 was one of the books held by Jesuits by 1911.

- C5: Marci's letter was held by the Jesuits by 1911.

- C6: Voynich ever got hold of BookA.

- C7: Voynich bought MS408 from the Jesuits.

- C8: Voynich got Marci's letter from the Jesuits.

- C9: Marci's letter was attached to MS408 when Voynich obtained it.

In particular, the only evidence for C2 is the signature on f1r; but that is not good evidence, because there is no record of the signature having been seen by anyone before Voynich obtained MS408.

Before we discuss the likelihood of these or other claims, it is worth noting the following features of probabilities:- P0. There is no certainty anywhere, only probabilities.

- P1. There is no such thing as the probability of an event. A probability is a numeric expression of the strength of one's belief in some claim, and therefore it is inherently subjective and personal. So there is only my probability, your probability, etc.

- P2. While Bayes's formula specifies how a rational person should change his probabilities of certain hypotheses on the face of evidence, it depends on his prior probabilities, and on his probabilities that each hypothesis produces observable consequences. Therefore, even after being presented with a ton of supposedly hard evidence, perfectly rational people can still have radically different probabilities for any hypothesis.

All the best, --stolfi

|

|

|

|