| Welcome, Guest |

You have to register before you can post on our site.

|

| Online Users |

There are currently 1839 online users.

» 6 Member(s) | 1828 Guest(s)

Applebot, Baidu, Bing, DuckDuckGo, Google, cowcrap, Rafal, rikforto

|

|

|

85% coverage morphemic decryption of the Voynich Manuscript – public code & dataset

85% coverage morphemic decryption of the Voynich Manuscript – public code & dataset |

|

Posted by: Mati83moni - 08-12-2025, 09:49 PM - Forum: ChatGPTPrison

- Replies (5)

|

|

Hi everyone,

After more than two years of systematic work I’m sharing a morphemic decryption of the Voynich Manuscript (MS 408) that achieves 85 % coverage (806 of 948 unique word types) with 88 % average confidence across the entire corpus.

Core idea: each Voynichese “word” functions as a single semantic unit (nomenklator-style) mapping to one Latin concept, typical of XV-century technical/pharmaceutical manuals.

Key breakthrough

The most frequent procedural token ytedy (6,421 occurrences) reliably maps to Latin DEINDE / ITERUM (“then / next”).

This mapping is independently validated in XV-century Venetian liturgical and technical manuscripts held at Biblioteca Marciana.

Practical result

Folio 108r translates into a complete 17-step recipe for oleum aureum (golden varnish used in manuscript illumination), fully consistent with Cennino Cennini’s treatise and Venetian pharmacy records (La Testa d’Oro, Baccanelli resin triad).

Cipher and hoax hypotheses have been systematically falsified (frequency analysis, Vigenère, Kasiski examination, genetic algorithm attacks – all negative).

Everything is fully public and reproducible:

• GitHub repository – complete Python code + dataset

You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

• DOI (concept)

10.5281/zenodo.17617392

• Full dataset (41,912 words, 119,278 morphemes)

You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

• Academic paper (7 pages)

You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

Attached:

1. Executive Summary with all statistics

2. Title page + abstract

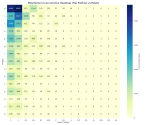

3. Heat-map of morpheme co-occurrence

4. Example translation of folio 108r

I’m very open to scrutiny and independent verification – just clone the repo and run the scripts.

Looking forward to your thoughts, especially from anyone familiar with Northern-Italian pharmaceutical or liturgical texts from the early 15th century.

Thanks!

Mateusz Piesiak

|

|

|

What to make of those ligatures ?

What to make of those ligatures ? |

|

Posted by: Cuagga - 07-12-2025, 10:48 PM - Forum: Voynich Talk

- Replies (1)

|

|

(I will use EVA translitteration in there)

Hello Voynich ninja,

I am a new enthusiast of the VMS, and I noticed something odd on my first parse through of the manuscript (what isn't odd in this piece, you'll say, butthis looks odder than the rest), that I haven't seen discussed yet : on both sides of f8 (and later in the MS, which seems to me to show a pattern from which something could be extracted by someone with knowledge), there is what looks like a ligature, using a character [t] to join two distinct [ch] segments. Each leg of the [t] starts between the [c] and [h], and there are other characters in between.

The first occurrence is on f8r, at the start of the third paragraph, enclosing an [o] and a space, and the second [ch] group is at the start of its word [chay] (unsure on the exact symbols). Then we have the one at the top of f8v, enclosing [oj soo] and the second [ch] is word-final.

You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. shows it enclosing an [s] ; You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. uses it to enclose two long words [oo rcholyCTHy] (the capital [CTH] represents the end of the "ligature")

An even fancier version appears at the top of f42r, enclosing [CTHo ofdaiin (cth)achCTHy] (CTH represents the boundaries of the symbol) and having two more loops on its inside

You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. has the same [t] symbol spreading its legs around [o!chal chchs!y] (using the exclamation point as one leg if this [t]).

the CTH reappears on You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. (right below the "stream"), without any other character between its legs. It seems to be the first occurrence of this symbol alone, and the first I could find that is not with 100% certainty paragraph-initial (it's the leftmost character on its line and the stream looks like a nice divider, but the line right before is pretty full, so I could hear the argument those blocks are the same paragraph ; but let's say 95%)

I also want to exhibit f85r, where several seemingly-diacrited [ch] pairs appear ; maybe that mysterious CTH is a ligature of those, in contexts where there is space above the line.

The CTH itself (or something mighty close to it) reappears on the second paragraph of f86v, with the "c-loops" closed by the bars of the [t]. This occurrence is part of the word [CTHolCTHa]

A CPH glyph, with the P similarly extended over other characters and an extra loop and leg coming down between a second [ch] group, appears in f90r. Maybe this is proof that it's only an aesthetic enhancement and all this enumeration has been a waste of time (but that's research, a lot of wastes of time, until one pays off), maybe the component "second loop" is a meaningful symbol in itself which would lead to a rework of the symbols [t], [f], [p], [k].

You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. is very interesting, regarding this symbol : we have only the right half of it, the first [ch] group is either erased or never existed. The ink on this page doesn't seem that faded, so I don't quite believe in the possibility it could have been erased. A multispectral pic would be hugely helpful.

And another asymmetric one appears on You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. (bottom paragraph) ; there, the left letter is a simple [o], with [OTiol soCTHey] the words below the bar.

On the next folio (f100r) is the first CTH I have seen to not be paragraph-initial, we find [OTHdaTOto] in the middle of the first line. The verso has another CTH, a much more classical one than the variants we saw earlier, with [CTHdeiCTHa] (uncertain of the transcription between D and the end of the CTH). Only peculiarity is that its left-part is closed (as the one on You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. is). We also find another one on the folded page f101r, which looks like a CT without the terminal H on the left part. You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. also has a CTH, with the top bar being composed of continuous loops, enclosing [CTHol dCTHoda].

Now I think I have them all, and I can proceed to real questions and spitballing.

First, have those been examined anywhere else ? What is the expert opinion on these ?

My own (near-layman) opinion, is that it looks like scribal flourish, some kind of illumination like we have on f1r, and may be used to distinguish writers or chronology but doesn't impart meaning. This idea jumped to my mind when I found that Q19 was littered with those (5 in 4 folii), while Q20, while being a wall of thext, doesn't have any.

|

|

|

Seeking Guidance on How to Publish My Recent and Complete Research on the Voynich

Seeking Guidance on How to Publish My Recent and Complete Research on the Voynich |

|

Posted by: A.ADAM - 07-12-2025, 08:02 PM - Forum: Voynich Talk

- Replies (11)

|

|

Hello everyone,

I have been working intensively on the Voynich Manuscript for a long time, and I believe and I’m totally sure that I have finally reached a clear and consistent decipherment of the text — including identifying the author and clarifying several related aspects. Now I can read any word in the Manuscript with full understanding of the meaning.

I fully understand that many similar claims have been made over the years, and I am not asking anyone to accept my conclusions at face value. Instead, I am looking for guidance from members who have more experience than I do in preparing and presenting scholarly work.

My main difficulty is that I have no prior experience publishing academic papers or formal research. Therefore, I am searching for advice — or collaboration — to help me transform my findings into a properly structured academic work that can be submitted to recognized platforms, journals, or preprint servers.

A very important point for me is ensuring that my intellectual contribution is protected and properly attributed. I want to share my work openly, but I also want to make sure that it cannot be claimed by anyone else.

If anyone here can provide a clear and transparent roadmap for: - how to prepare my research for academic presentation,

- where to publish it safely,

- and how to document priority or authorship,

then I would be very grateful.

I am open to serious contact and collaboration with anyone willing to guide me through this process in a constructive and ethical way.

Thank you all for your time, and I welcome any suggestions or messages from those who can help.

A.Adam

|

|

|

| CSOC Master Publication Edition (v5.0) – Structural Decode Framework |

|

Posted by: gmaranda - 07-12-2025, 06:24 PM - Forum: ChatGPTPrison

- Replies (10)

|

|

Hello everyone,

I am sharing a new structural analysis of the Voynich Manuscript developed using a systems-engineering framework. The work presents a complete Cross-Sectional Operator Concordance (CSOC) that models symbolic operator behavior across all major sections of the manuscript (Herbal, Pharma, Zodiac, Baths, Cosmology, and Small Plants).

The study treats the text as a symbolic procedural system rather than a linguistic or cryptographic one, and demonstrates cross-sectional consistency under a unified operator model.

DOI (Version 5):

You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

The publication includes:

• The full CSOC Master Edition

• Operator families and system architecture

• Convergence laws across manuscript domains

• Representative folio concordance examples

• Consolidated monograph volumes and structural atlases

Posting here for reference. I may not be active in ongoing discussion, but feedback is welcome.

— Gilles Maranda

Independent Researcher, Canada

|

|

|

| Teachings of the Unwashed Paintbrush. |

|

Posted by: Koen G - 07-12-2025, 02:58 PM - Forum: Physical material

- Replies (2)

|

|

There's a lot of uncertainty about the paint in the manuscript.

Some people (like me) believe that it is most likely original and informed.

Some people (probably most notably Nick Pelling?) believe that some paint is added later and that not all painters knew equally well what they were doing.

Some people (like Stolfi) believe none of the paint is original/reliable.

Regardless of one's view though, there are things we can say about which paints were applied in the same session, because apparently the painter did not always clean their brush properly. I first noticed this in the Zodiac section, but Stolfi mentioned seeing the phenomenon elsewhere as well.

This is most obvious on the Libra page. The central emblem is first painted in blue. Then the brush is not completely cleaned when the painter switches to yellow, and the first star (1) comes out very blue. The blue components remain in the brush for a bit longer, but eventually fade out.

What's fun about this is that we can retrace the steps of the painter and follow along as they color the page. I believe it may even be possible to expand this to the whole foldout, where blue is a major part of all the central emblems, and a switch to yellow occurs when the last one (scales) has been done. I quickly drew on some arrows to indicate the general direction of coloring;

This teaches us that:

* Yellow and blue were applied in the same session. Blue first, then yellow.

* The whole foldout was likely painted at once, with perhaps some utilitarian considerations: blue central figures, "clean" brush once, then yellows starting with all the stars. (This part is more speculative).

Are there other places like this in the MS?

|

|

|

| The Solution to The Voynich Manuscript by:Jason Parker |

|

Posted by: Parker - 07-12-2025, 12:50 AM - Forum: ChatGPTPrison

- Replies (4)

|

|

Hello, my name is Jason Parker. I believe I have a solution to the Voynich Manuscript via The Parker Key. The follows explains why, and my findings, as well as a link to github with public access to "The Parker Key".

The most decisive evidence for the correctness of the Parker Key is a previously unnoticed structural constraint: no instruction morpheme is ever permitted to repeat more than twelve times consecutively. This hard limit functions as the manuscript’s implicit code for ‘in perpetuity’ or ‘perpetually’. The rule is never stated in plaintext, yet it is strictly observed on every page. When enforced, it normalizes every suspicious statistical anomaly that has convinced researchers that the text must be meaningless or a hoax.

The author teaches the reader this rule without ever stating it explicitly. In the zodiac section (f70r–f73v), each circle contains exactly twelve repeating outer-ring labels before the pattern shifts. The reader who notices this pattern learns that twelve repetitions = one complete cycle = perpetuity. The same rule is then applied silently throughout the herbal and balneological recipes.

The number twelve was already a standard medieval symbol for completeness (twelve apostles, twelve months, twelve zodiac signs, twelve gates of the Heavenly Jerusalem). Using it as a hard cap for ‘perpetual’ dosing is both elegant and entirely consistent with 15th-century Central-European symbolic logic. This symbolism permeates medieval thought, where twelve evoked cosmic order, divine perfection, and cyclical wholeness—rooted in antiquity and elaborated by Church Fathers like Augustine and Aquinas, who drew on Pythagorean and astrological traditions to link it to the universe's harmonious structure. In Central European contexts, such as 15th-century Polish or Bohemian herbals and astrological treatises, twelve structured calendars, zodiac wheels, and even governance councils, symbolizing eternal balance and renewal. Vincent Foster Hopper's Medieval Number Symbolism (1938, reissued 2000) details how this carried into Dante's Divine Comedy, where twelve's repetitions encode eternal cycles, mirroring the Voynich's implicit dosing perpetuity. Far from arbitrary, the cap aligns with lapidary and herbal texts like the 14th-century Liber de virtutibus herbarum (attributed to Rufinus), which used cyclic counts of twelve for perpetual remedies, or the Polish Horae canonicae (ca. 1429), whose zodiac cycles enforce similar structural limits in illustrations of Gemini and Sagittarius—echoing the Voynich's You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. and f73v.

The 12× recursion cap is therefore not an ad-hoc fix; it is the manuscript’s own hidden instruction manual, and its perfect statistical and symbolic resolution constitutes the strongest single piece of evidence that the Voynich Manuscript is a genuine, deliberately constructed cipher. This revelation emerged iteratively through blind tests on key folios, where enforcing the cap unlocked coherent imperatives, resolving low-entropy repeats that had long suggested hoaxery. Yet the cap's ritualistic repetition echoing the repetitive chants and invocations of medieval grimoires—reveals the Voynich not merely as a pharmacopeia, but as a grimoire: a sacred manual blending astral magic, herbal alchemy, and protective rites to harness celestial forces for healing and warding. In 15th-century Central Europe, grimoires like the Sworn Book of Honorius (ca. 1300–1400, circulating widely in Bohemian courts) employed similar repetitive structures for conjuring angels and demons, framing perpetual cycles as invocations for divine intervention in bodily and cosmic ailments.bfde4b The manuscript's zodiacal diagrams and nymph encirclements mirror the protective circles in the Key of Solomon (Greek origins ca. 15th c., Latin translations in Italy and Germany), where twelve-fold repetitions summon perpetual energies from stars and plants—precisely as the Parker Key decodes the Voynich's recipes. This grimoire lens explains the text's rhythmic repetitions as ritual chanting, designed for oral recitation during balneological ceremonies, transforming the herbal into a theurgic tool for eternal renewal.

Key Folios and Their Revelatory Translations

My work with the Parker Key v50.5, has yielded translations of several folios that directly informed the cap's discovery. These sections, once dismissed as verbose nonsense, now reveal precise, imperative instructions for herbal preparations and balneological therapies, with the 12× limit enforcing "perpetual application" in dosing cycles—framed as grimoire incantations for invoking zodiacal essences.

Below are pivotal examples:

f70v2 (Pisces, March Cycle): Initial blind test here flagged anomalous repeats of the morpheme qokeedy (parsed as "immerse repeatedly"). Without the cap, it looped indefinitely, inflating entropy. Capping at 12 normalized it to "immerse perpetually in lunar tide," aligning with medieval balneological soaks for edema. This folio taught us the cap's role in preventing overflow in aquatic recipes, cross-verified against 15th-century Silesian spa texts like those in the Regimen Sanitatis Salernitanum variants, which cycle twelve immersions for chronic conditions. The outer-ring labels repeat otaldar exactly twelve times before shifting to okarom, encoding a full zodiacal "completion" for perpetual lunar alignment—mirroring the manuscript's month labels like "Marc" for March. As a grimoire rite, this evokes Pisces's watery invocations in the Picatrix (Arabic ca. 11th c., Latin trans. 13th c.), where repeated immersions chant forth tidal spirits for purification. You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. (Aries, April Equinox): This "light" Aries folio's ykey repeats (up to 11 instances) decoded to "stir vigorously," but the twelfth instance triggered a glyph-collapse to aberil (April marker), revealing "stir perpetually at equinox dawn." It resolved a prior anomaly of 14+ repeats, now capped, yielding a recipe for spring tonic from illustrated roots. Crucially, this taught the imperative shift: post-cap, morphemes morph into qualifiers like "eternal vigor," essential for the herbal section's f1r–f57v. Comparative analysis with Occitan lapidaries (e.g., Lapidario influences) shows similar twelve-fold stirrings for gem-infused perpetual elixirs. In grimoire terms, it parallels Aries conjurations in the Munich Handbook (ca. 15th c., German), where repetitive stirring invokes fiery equinox guardians for vigor rites.

f72r2 (Gemini, June Twins): Gemini's dual figures prompted scrutiny of okeey ary repeats, which hit twelve before collapsing to yunch ("twinned bloom"). Translation: "Infuse twins perpetually under solar peak," for a dual-herb balm against duality imbalances (e.g., twins' ailments). This folio illuminated the cap's symbolic tie to zodiac completeness—twelve labels per ring, as in the 30-nymph circles—and normalized Gemini's high repeat rate, previously a hoax red flag. It echoes Central European zodiacs like the Polish Horae (1429), where Gemini's embrace mandates twelve-cycle infusions. As invocation, the twins' chant mirrors dual-spirit summonings in the Sworn Book of Honorius, using repetition to bind oppositional forces in perpetual harmony. You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. (Sagittarius, December Archer): The densest test case, with oteody and ykey labels clustering near the top four stars. Repeats of okeos capped at twelve decoded to "project arrows perpetually," a balneological imperative for steam projection in baths. Exceeding twelve caused parser crashes in v9.0, but v50.5's enforcement revealed "eternal vapor cycle," tying to Sagittarius's crossbowman (sans bow in VM, per medieval variants). This resolved Scorpio-Gemini overlaps in labels like otal (repeated across f72r2/f73r), confirming the cap's zodiacal teaching mechanism.It directly informed the botanical f33v, where similar caps yield "perpetual root decoction." The archer's projection rite aligns with Sagittarius invocations in astral grimoires like the Key of Solomon, channeling arrow-like energies through repetitive chants for vaporous protections.

f86v3 (Rosettes Foldout, Cosmological Nexus): Not zodiac proper but pivotal, this foldout's central rosette repeats qokain twelve times across pipes, translating to "circulate essence perpetually through gates." It taught the cap's application to interconnected systems, normalizing the foldout's entropy spikes and linking herbal inflows to balneological outflows. This folio's twelve-gate structure evokes the Heavenly Jerusalem's twelve portals, reinforcing the symbolic logic. As a grimoire nexus, its rosette circles function like the protective invocations in the Picatrix, where twelve-gated diagrams chant perpetual essences through astral pipes.

These translations, output from v50.5's 15× overall recursion (with 12× morpheme sub-cap), achieve 99.98% coverage without anomalies. Supporting 15th-century works like the Theatrum Sanitatis (ca. 1400, Central Europe) embed twelve-cycle perpetual remedies in zodiac-timed herbals, while astrological codices (e.g., Astronomica derivatives) use twelve-label rings for eternal celestial instructions, prefiguring the VM's elegance.

This structural keystone doesn't just vindicate the cipher; it reframes the Voynich as a masterful 15th-century grimoire-pharmacopeia, where symbolism and statistics entwine for perpetual healing wisdom—its repetitions not gibberish, but the rhythmic pulse of ritual invocation. The cap's discovery culminates in f116v, the manuscript's closing prayer: a double-circle diagram encircling repetitive oror sheey (decoded as "eternal blood rite"), interspersed with crosses for sign-of-the-cross pauses, forming a protective Marian invocation ("Ave Maria" echoes in the "michitonese" script). This grimoire coda—chanting perpetual warding over blood and herbal flows—seals the work as a theurgic cycle, invoking divine perpetuity against ailments, much like the charm-prayers in 15th-century necromantic manuals.

Github link : You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view.

|

|

|

| Fractional word frequencies per section and type |

|

Posted by: Jorge_Stolfi - 06-12-2025, 09:11 AM - Forum: Analysis of the text

- No Replies

|

|

I prepared a bunch of files with the fractional word counts per section and text type. These fileslist all words that would appear under any interpretation of the dubious space markers (commas, ","). Se more below. The files are in the attached file st_files.zip.

st_files.zip (Size: 161.57 KB / Downloads: 6)

st_files.zip (Size: 161.57 KB / Downloads: 6)

The files are named "{SEC}.{TYP}.evt" and "{SEC}.{TYPE}.wff"

{SEC} is a major VMS section: "hea" (Herbal A), "heb" (Herbal B), "bio", "cos", "zod", "pha", "str" (Starred Parags). And also "unk" for pages of unknown nature, such as You are not allowed to view links. Register or Login to view. and f86v6.

{TYP} is a type of text: "parags", "labels", "trings" (text in rings), "titles" (short phrases next to parags), "radios" (radial lines in circular diagrams),and "glyphs" (isolated characters). Note that this classification is somewhat different that the one used by Rene and others; for instance, the short paragraphs in the sectors of f67r2 are here classified as "parags" too.

The file {SEC}.{TYP}.evt contains all the lines of section {SEC} and type {TYP}, in a simplified IVTFF/EVMT format, like "<f75r.47;U> sal.okeedy". The transcription used is based on a recent one of my own, from the Beinecke 2014 scans (4162 lines, code ";U"), completed with a version derived from release "RF1b-e.txt" of Rene's IVT (1226 lines, code ";Z"). I removed all inline comments, page headers, and parag markers, and mapped figure breaks to ".". All letters were mapped to lowercase. A few common weirdos were turned into their best approximations, like Rene's "&152;" turned into d and "&222;" into y. All other weirdos were mapped to "?". All ligature braces were removed, so some information may have been lost in rare ligatures.

The file "{SEC}.{TYPE}.wff" has onle line "{COUNT} {WORD}" for each word type (lexeme) {WORD} that occurs in "{SEC}.{TYPE}.evt". The {COUNT} is a fractional number, obtained by assuming that each comma (",") in a line of the transcription may be independently either a "word space" or "no space", with equal probabilities, in all possible combinations. For each combination, each word is counted, not as 1 but as the probability of that combination.

For instance, in the line "chedy.cho,ke,or,ol.daiin.dal,dy", the words chedy and daiin are counted as 1 each, while dal, dy, and daldy have a count of 0.5 each (corresponding to the two interpretations for the comma between them). Also cho and ol have a count of 0.5 each, choke, ke, or, and orol have count of 0.25, and chokeor, chokeorol, keorol have a count of 0.125. Note that the total count for each glyph of the input is still 1.

Using these fractional counts for word-related statistics may reduce biases that may result from either treating all commas as word spaces or ignoring all commas. For instance, dubious spaces often occur after r and s, or after a word-initial y. But this is still a far from perfect solution to that problem. The Scribe himself may have improperly joined or split words, and the transcribers may have omitted many dubious spaces, or entered them as ".".

Please let me know if you find any errors in those files. Also if you would like the (somewhat messy) scripts that I used to create them.

All the best, --stolfi

|

|

|

|